On (a) Wim

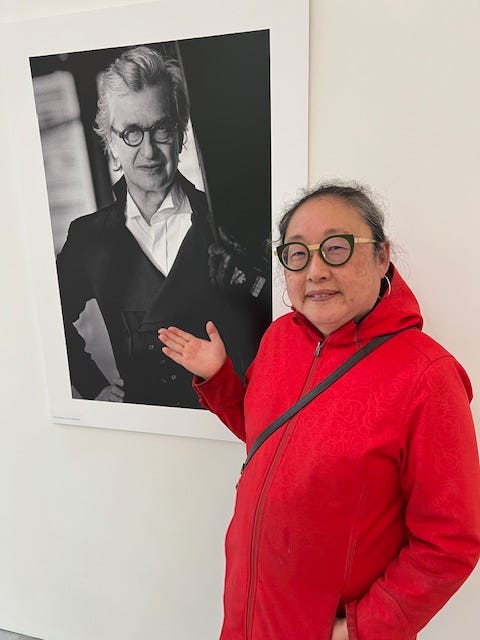

Letter to a Film maker son on the Photography Exhibit by Wim Wenders in Berlin

Dear Kenji,

Greetings from Berlin! I’m writing here on Substack instead of sending you a handwritten letter in which I would find it troublesome to explain all that I encountered recently in a gallery exhibit of Wim Wender’s photographs called Nearby and Far Away.

On a rainy Saturday afternoon, your father and I headed out to Bastian Gallery on Taylorstrasse. We had to take the U3 subway line which has some of the oldest and prettiest stops of the Berlin Metro.

At a quaint country cottage-looking like station, we got off the train and headed in the direction of the gallery. We walked along a broad boulevard and an area of suburban condo-like residences. At one point across the boulevard, we could see the large and rather imposing edifice of the American Embassy. It looked so big and ugly that I paused a moment wondering whether or not I should take a photo. But we trundled on.

The gallery was not far past the Embassy and it was non-descript. ‘Non-descript’ is one of my favorite words for describing buildings — especially those in North America where the architecture seemingly everywhere is just that — non-descript. But to be clearer and descriptive, I shall say the gallery was a square white building situated at the edge of a green space.

Contemporary art galleries like this remind me of white paper cubes, the kind you can make with origami. Imagine walking into such a cube — all around you are walls of white spaces — with just a few select photographs hanging at eye level. This was my experience of this particular photography exhibit.

Now, much can be said of the medium of photography as way of presenting images. But let me speak more technically here. This exhibit is of photography where the images are printed with an inkjet printer onto archival paper and are presented in physical frames on walls which you can then peruse in sequence, or out of sequence, in a physical space — a building.

It’s virtual reality in situ. No, let me re-word that. It’s reality, in situ. And what my words are, are interpretive descriptions of that reality-in-situ, in words (re: not images.)

***

As you know, photography and film are different mediums, but they are closely related. Many filmmakers start their careers as photographers. Photographers are interested in capturing a moment in an image. Filmakers, however, are interested in narrating a story in time through images. Videographers, it seems run the gamut between these two expressions — a moving image of tree branches shaking in the wind — may be interesting to look at the first time — but a series of such moving images might easily become boring for some, unless you’re really pre-occupied or obsessed with representing the movement of trees through time. These kind of videographers I call paintographers and admittedly I’m not a great fan of this kind of videography. The other kind of videographer is the one who is narrating a story with an arc to it. For example, in Wim Wenders’ film, Perfect Days, Wenders’ presents a character obsessed with trees and their movements above him in a canopy when he takes a lunch break in a nearby park at his job as a public toilet cleaner in Tokyo. In the film, you do get a shot of the waving tree branches, but they are not the subject of the film, but rather the subject of the protagonist’s gaze who himself is the subject of the filmmaker’s story.

In Wim Wenders’ photography exhibit, I felt that, as ‘painterly’ as the images were, there was still an undercurrent of a story behind them. The main ‘character’ of this story is Wenders’ himself, and what he is narrating here in the sequence of presented images are his ideas.

This photography exhibit has ten photos. When you enter the foyer section of the gallery, you are presented with three photos of the forest in which shafts of light illumine objects and shapes in the forest like the moss on the ground or the pillar like shapes of the trees. These photos are simply titled Wald I, III and IV. Wald is the German word for ‘forest.’

The rest of the photos in the main part of the gallery are taken in China, and subsequently titled with the words ‘China’ and a number. There are only seven of these photos and four of them are taken in the Gobi Desert. Almost all of the photos feature people in them, many of them taking selfies or gazing at their phones. There is only one photo without a person, and that is of a dune. The image of the people-less dune attracts me enough that I try drawing it on my phone.

***

In the exhibit notes, it says of Wender’s forest photography:

Wim Wenders sees the magical light phenomena from the deep centre of summer, the romantic forest that was once the untouchable cathedral of longing for the Germans, in which the young Goethe wrote the dreaming Wanderers’ Night Songs in 1780.

When I looked at those three photos of the forest, I was taken back to Canada. The forest is a place Canadians know. That shaft of light through the trees in the ‘deep centre’ of summer is how many of us experience nature in Canada. It is, for many of us, too, the ‘untouchable cathedral of longing.’ For you, Kenji, such an experience is one you might have well had in your years at Manitoba Pioneer Camp first as a camper, then as cabin leader, and finally as camp videographer.

And as for the photographs in China with people looking on their cellphones, sure, it’s gentle satire, but these photos are also a commentary on ourselves and where our gaze is directed.

The phone-as-camera/video allows us many things, many indulgences, but what are we truly looking at? What do we think is memorable? What do our photos really say about us and to whom, in particular?

In this gallery, there are two windows. Both are long and rectangular and run from the bottom of the floor to the top of the ceiling. The one window facing the street had a white sheet covering it, held up by black binder clips. The other window had a view to the park which was green and lush.

The photograph beside the window inspired me make this short video essay:

Agnes Varda has coined a word I find very apt for filmmaking — cinecriture. Cinecriture is cinematic writing. If I were to script this video it would read as follows:

A long queue of people are climbing a vast sand dune like ants. Their goal is to reach the top of the dune. What will they see when they get there?

(Pan back from photographic image to reveal that it is in a frame in an art gallery) then slowly move camera back to reveal the placement of the photograph on the gallery wall to the window which reveals the lush greenery of the outdoors.)

***

I wonder how Wenders decided to arrange the photographs in this gallery. It’s possible he might have expected viewers to enter the main part of the gallery first and see the photographs of China (presumably referring to the ‘far away’ of his title) and then see the forest photographs afterwards (the ‘nearby.’) The sequence of one’s viewing will affect one’s experiences and perceptions. I have only given you my experience here, Kenji, of what I saw first — Wald — and then China.

Short story writer Alice Munro talks about how she takes a reader through the journey of her story from a certain entry point as if the story were a house; your reading of the story, therefore, will be greatly affected by where you enter it.

Story reading and interpretation is linear. But movement in a three dimensional space is not. You, the viewer, make up the narrative as you go along. This thought reminds me of something I read about how to arrange poetry in a book. Poems are like paintings or photographs — they are one-ofs — and how you arrange the poems in a book is like how you would arrange paintings or photographs in a gallery. The title would then encapsulate in a cumulative way, the whole experience as in Wender’s title “Nearby (Wald) and Far Away (China.)”

When I write stories, I’m a filmmaker. When I write poems, I’m a photographer.

Kenji, do you remember making your stop-motion Lego films? I do. I was always struck by how you used Lego primarily as sets for your stories. You weren’t interested in making fantastic structures or buildings like some of your friends.

You might think of those ‘sets’ now as your ‘photographs’ in the way Wenders has in his exhibit. Wender’s photographs are clear, crisp, and defined images. They are representative art. Not abstract. They do not question the lens, the mechanism, the medium as other post-modernist artists might do; Wenders is perhaps old fashioned that way.

The photographs then can thus be interpreted as ‘sets’ or ‘settings’ for a certain kind of reading.

One interesting technical observation I made which I mentioned already is the absence or presence of humans in his photos. The Wald photos are of pure seeing. The China photos with the exception of the Gobi desert one are of other people seeing (mostly into their phones.)

***

There is one photograph in this exhibit that made me think of you. It’s of an oasis in the Gobi desert. Awhile back, I began writing snippets of something that might turn into a novel. It features a character much like yourself contemplating his mixed race identity by trying to imagine what landscape would be its metaphorical equivalent. The book’s tentative title is: The Central Plains of Asia.

Here’s a snippet from the narrator:

My mom likes to say I’m from Kazakhstan which isn’t true. I’m really from Alberta. But for Mom, Kazakhstan is not a real place; it’s a place in her imagination like how China was and is for most people, except the Chinese.

Nearby (Wald). Far Away (China).

I’ve been to China, but not the part of China Wenders photographed, except for that oasis which I visited in my imagination as I researched this place on the internet. I recognized Wender’s photo as being of the ‘famous oasis of Dunhuang with singing sands and crescent-shaped lake’ which according to Google is ‘rightly considered the biggest tourist center in the north-west of China.’

I must say, I was gob-smacked by the sheer coincidence of this photograph depicting a place I’ve been obsessed by for my fiction.

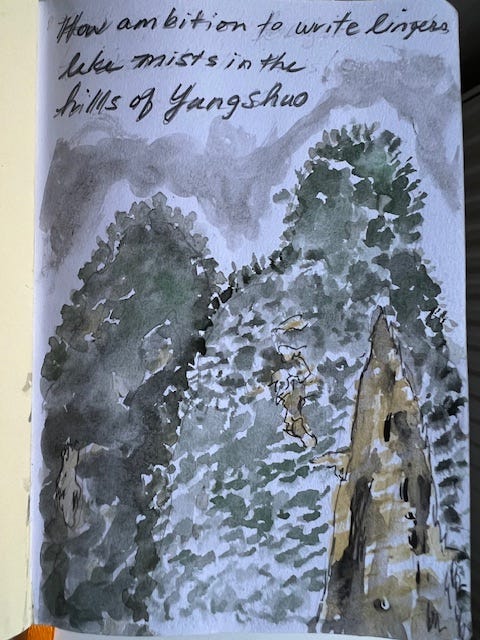

When I was in China, I visited Guilin. Guilin is famous for it’s narrow almost cylindrical shaped mountains of the kind you’ve probably seen depicted in Chinese paintings.

Every day I would walk outside and pinch myself for actually being in a place I had considered imaginary. After that trip, when I went into a Chinese restaurant and saw a painting of those strangely shaped mountains, I recognized a place an artist had rendered. In fact, many times I rendered those mountains myself in my little haiku journal.

The imagination is a powerful tool for actually being in a place you’re not. Recognition, on the other hand, is an affirmation of an artist’s skill in representation and rendering. Imagination and recognition don’t necessarily have a connection with each other, but somehow I feel these concepts are related and I’m trying to work out in words why.

In my novel, the Central Plains of Asia, the setting or location is a metaphor. In Wenders’ photography, the photos of the Gobi desert also work, I think, as metaphors analgous to his other photos of the forest.

What are the people in the Gobi Desert doing in Wenders’ photos? They are sight seeing (like Wenders himself), they are ‘seeing’ their phones or seeing themselves in their phones, or they are seeking something by climbing up a famous dune.

I have repeated the word ‘see’ four times, the last word of which ‘see’ is a part of the word ‘seeking,’

There is one photo of the desert without people in it. There are three photos of light in the forest with no people in them.

What sensation and connotations do the words ‘light,’ forest,’ ‘desert’ and ‘no-people’ (aka ‘selfless’) evoke in your mind?

Photo-criture. That is what I am doing in this letter. Changing images into words and then changing the words again into something else.

***

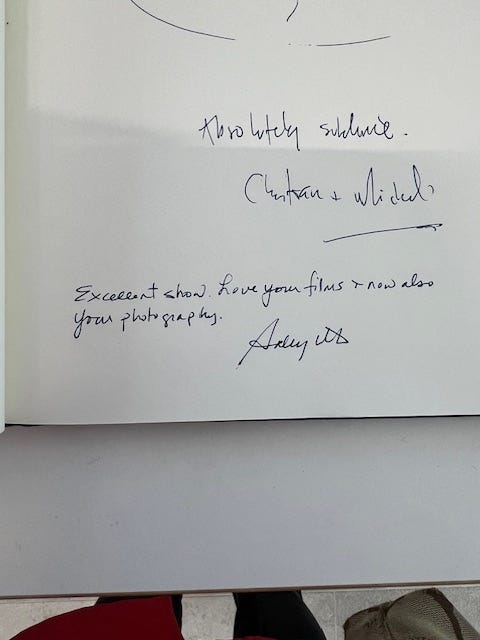

Thanks, Wim Wenders, for rendering so faithfully a place that synchronously evoked for me an imaginative landscape of my own rendering (through research, of course.) That photograph of the oasis in the desert, in particular, is what inspired me to write this post as a letter addressed to you, my beloved son! Handwriting a letter though, would have been just hard and I could not have done all the associative linking of images and ideas without literally cutting and pasting gallery info sheets and jotted down journal notes into a letter that would cost more time and effort to mail than by Googling for information and hitting the ‘send’ button.

A Substack post is digital, and by being digital, gives me all the more lassitude to share things in different mediums than would be possible in a hand-written or typed document. But I still prefer the letter form — the epistolary —because it’s personal and intimate, and in that sense perhaps reflects a process that is uniquely human to me. I say this all because we are in danger of a time where AI will, if we let it, do the feeling, sensing, thinking for us. It will give us other peoples’ ways of ‘feeling, sensing, and thinking’ that we will mutely recognize but will not have created ourselves. There is a terrible danger in this, especially for a young person. Putting things into words or drawing a picture or taking photographs is something humans do. Doing all of these things at first badly or poorly is to be expected. Then comes the next (human) act of editing, revising, transforming a creative work to make it better or to sharpen one’s vision or develop a voice or style. This is the artistic process which is critical for every artist to undergo.

Now, having said that and despite what I have written here in this expansive digital medium, this letter will not in any way feel as real as going to the exhibit and experiencing it personally yourself. This letter is merely a record, a documentation as well as an interpretation of and response to what I saw, felt, heard in that gallery. It was written out of an impulse to explore, investigate and ponder in words what I’d seen to you because I love you and the artist you are becoming.

So, I guess, in conclusion, what I have written here is a love letter! But not just to you, but to my readers, and of course, to Wim Wenders, the artist.

Incredibly perceptive, about artistic endeavors not so familiar to my (word-centered) brain. Thank you, Sally.